Kawerau Earthquake Swarm

Written by John Grant on March 19, 2023

By GeoNet

Since the earthquake swarm in Kawerau began in the early hours of Saturday 18 March, we have located over 600 earthquakes including eight earthquakes over magnitude (M) 4. Many of these have caused felt shaking in the area, and many more won’t have been noticeable to humans – just to our seismic monitoring equipment! The largest to date has been M4.8 and the majority have been between M2.0 and M2.9.

Earthquake swarms are quite common in New Zealand. While they may sound scary, swarms are just a collection of quakes about the same size, happening in a localised area, usually over a short time period (hours to days to weeks). Swarms usually don’t have a mainshock or larger quake that starts off a sequence.

The current earthquakes in Kawerau are in keeping with historic activity in the region, with previous swarms occurring in 2018 and 2019. These both comprised several hundred recorded events in total and lasted for several days. Swarms are a common feature of the Central Volcanic Region in New Zealand, although swarms with this number of M4 events are relatively infrequent.

We know the shaking has been disruptive and disconcerting for folks in the area. Our teams continue to monitor the activity and the most likely scenario is for the swarm activity to continue decreasing over the next few days.

The National Geohazards Monitoring Centre at GNS Science keeps a 24/7 watch on the four main perils in Aotearoa – earthquakes, landslides, tsunami, and volcanoes – and will be continuing to follow this swarm activity closely.

Why are these earthquakes described as light shaking?

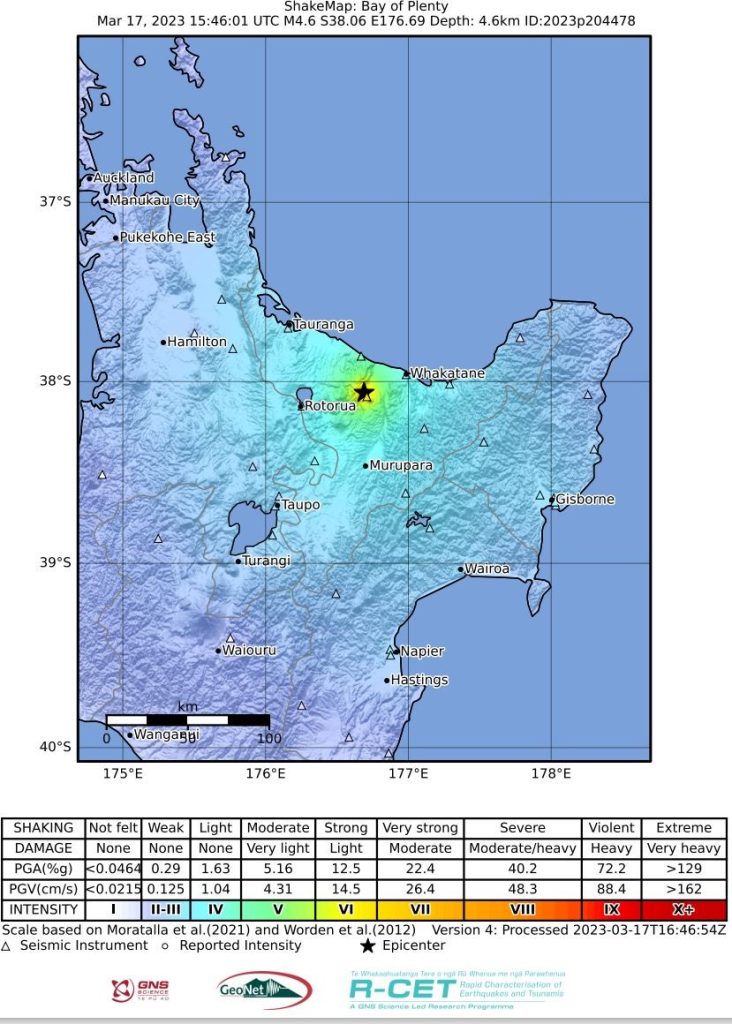

The designation of ‘light shaking’ is calculated by an automated system and is based on the earthquake parameters and converted to Modified Mercalli intensity scale.

Shaking varies quite a lot based on where you are when the earthquake happens. For folks closer to the epicentres of these quakes, or on softer soils, their shallow depth may have made some of them quite a rumble. As you can see from the shakemap below, for the M4.8 (which was designated a ‘light’ shaking intensity by the system) shaking for those closer to the epicentre of the earthquake was strong.

Is this swarm related to volcanic or geothermal processes?

Is this swarm related to volcanic or geothermal processes?

Given the tectonic setting, history of swarm activity, and the normal-faulting mechanisms identified for some of the larger events, it’s most likely that this swarm is tectonic in nature. Although it is a geothermal area, it would be very rare for geothermal activity to lead to such large magnitude earthquakes. The location of the swarm is outside a volcanic area, so there is no indication of volcanic unrest, and no relation to the recent unrest at Taupō or Ruapehu.

Will this swarm lead to a larger earthquake?

We can’t predict earthquakes, so we can never say with certainty that a larger earthquake won’t occur – these are the shaky isles! However, by far the most likely scenario is that the level of seismic activity will decrease over coming days-to-weeks.

What fault line is this activity associated with?

For earthquakes of this size we don’t regularly associate them with a particular fault, partly because of uncertainties on the seismic parameters (location and depth), and partly because even fairly small fractures can host events like these. However, there are many faults and fracture systems mapped in this area, which is to be expected for the tectonic setting.

Is it possible that I can hear the earthquakes?

Yes! When a small earthquake is very shallow and very close, people can sometimes hear it without feeling it. The first wave arriving from an earthquake is a P (primary) wave, which is a compressional wave similar to a sound wave. When this wave reaches the ground surface from below, it can produce a sound wave in the air that people hear. This effect is more pronounced in valleys, where the sound can reverberate off nearby hills.

What’s the risk of landslides from these earthquakes?

There has been some landslide activity in the area related to these earthquakes, including rockfalls. This extent of landsliding is to be expected for M4-5 earthquakes. The ground is likely more vulnerable to landslides now due to the recent cyclone and rain, and there are many landslides still visible from Cyclone Gabrielle.

Landslides can be triggered by heavy rain or earthquakes and can occur with little or no warning. Some can occur without any obvious trigger. Homes near hills or steep slopes and cliffs are most at risk – so if that’s where you live, watch out for cracks or movement that could be a warning sign, and get quickly to safety.

Follow Civil Defence’s advice on what warning signs to look out for so, you can act quickly if you see them. Contact 111 if you are in immediate danger or otherwise call your local council.

Although we can’t prevent natural hazards, we can prepare for them – and we should.

Know what warning signs to look out for, so you can act quickly. Drop, Cover, and Hold during a large earthquake. If it is Long and Strong, Get Gone! People near the lake front should move to higher ground as soon as it is safe to do so, especially if they hear loud noises or see unusual lake action during earthquake activity.

If you are near or on steep slopes or cliffs, keep an eye out for falling rocks and cracking.

All New Zealanders should be prepared in case of a natural disaster-induced emergency. Follow the National Emergency Management Agency’s guidance on how to make sure that you and your whānau will get through an emergency. For information on how to prepare your house for earthquakes, check out Toka Tū Ake EQC’s advice for homeowners and renters.